It is impossible from the outside to tell where the negotiations are headed. But what I want to try to do here is offer some suggestions for how we could think about the gap, how we got here, and what we might do in the future to alter the conditions that have created what is undoubtedly a crisis at the University, and a depressing foreshadowing of the end of UC as a serious research university. If the latter does happen the responsibility will ultimately lie with UCOP and the Regents with some support from the campus Chancellors.

The first point is that it seems clear that there is a fundamental gap in the way that each side is defining these negotiations. UC is approaching this as if it were a conventional labor negotiation with a class of workers whose position is fundamentally stable. The UAW and its supporters on the other hand, start from the position that they have been placed in an untenable economic position. Given the fact that TA wages have barely kept up with national inflation over the years combined with the extreme cost of housing in California, they cannot continue with relatively minor adjustments in the dollar amount of their monthly pay. To make matters worse, UC's latest offer has a first year adjustment that is about equal to current inflation. In this light, UCOP appears completely out of touch with the reality of life on campuses and indifferent to its lack of knowledge.

This image of autocratic disregard was only deepened by Provost Brown's appalling letter to the faculty last week. Although much of it was standard UCOP pablum, he inspired widespread faculty hostility with his closing flourish threatening faculty members who refused to pick up the work of striking workers with discipline beyond the docking of pay. For the last three years, faculty and lecturers have performed an enormous amount of additional labor to keep the university afloat during the pandemic: transforming their courses, spending additional time with students, planning for campus transformations, and putting their research duties on the side to maintain "instructional continuity" as the administration likes to put it. After all this effort, for the Provost to threaten disciplinary action for those who choose not to pick up the work of striking TAs or to act upon their own convictions about academic integrity, manifests a contempt for the faculty that is hard to ignore.

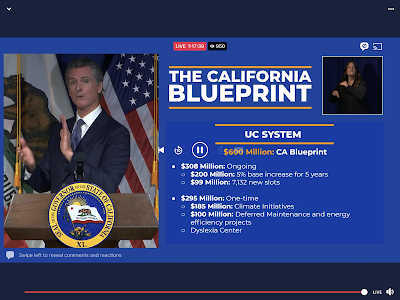

It's important to grasp UC's budgetary situation correctly. Most importantly, the usual invocation of the university's 46 billion dollar budget needs to be put aside. Most of that budget is tied up in the medical centers or in funding for designated purposes. The real budget that is relevant is the core budget made up of tuition, state funding, and some UC funds. It comes in closer to $10 billion (Display 1) and is largely tied up in salaries across the campuses. As Chris and I have been pointing out for nearly 15 years, UC has been subject to core educational austerity surrounded by compartmentalized privatized wealth (although we should notice that the medical centers barely stay in the black). This crisis will not be overcome by hidden caches of money floating around the university. The problem is deeper than that: its roots lie in the combination of state underfunding and the expansion of expensive non-instructional (often non-academic research) activities that have taken up too much of campus's payrolls.

But I want to stress that this reality does not mean that the graduate students are being unreasonable in seeking wages that enable them to perform their employment duties and pursue their studies. Instead, it is a sign of how deep the failure of the University has been in (not) providing a sustainable funding model both for students and faculty supporting students. The Academic Senate has been pointing to this problem for at least two decades. In statements and reports from 2006, 2012, and 2020, the Senate has repeatedly insisted that graduate student support was insufficient and proposed steps to improve it. Even the administration itself has sometimes recognized its depth. To take only one example from 2019, UCOP's Academic Planning Council declared that:

UC must do better at financially supporting its doctoral students, particularly as it seeks to diversify the graduate student body. The University cannot compete with its peers for talented candidates if it does not offer competitive support. In 2017 the gap in average net stipend between UC and its peers was nominally $680.3 In actuality the gap is much greater due to California’s high cost of living - with factored in, the average gap in doctoral support is closer to $3,400.4 This is a huge difference but not insurmountable. The Workgroup urges UC leadership to make every effort to close the gap so that the quality of UC’s doctoral programs is maintained and enhanced.

UC campuses, with planning and prioritization, could guarantee five-year multi-year funding to doctoral students upon admission. According to current data, about 77 percent of doctoral students across UC receive stable or increasing net stipends for five consecutive years.5 (Appendix 1.) With some exceptions, this multi-year funding is relatively consistent across campuses and disciplines. However, this funding is typically not presented as a full five-year multi-year guaranteed package upon admission. Offering five-year funding upon admission would enhance recruitment of high-potential students, offer financial security, and address one of the chief stressors for doctoral students - worry over continued funding while in the program.

In addition to offering guaranteed five-year funding, the University must address the issue of graduate student housing. Graduate students, many of whom have family responsibilities, face enormous challenges in finding affordable housing. Without a targeted effort to address graduate student housing, UC’s capacity to attract and retain qualified candidates is at serious risk. (4-5)

And yet the problem persists. The Academic Senate has stressed this issue repeatedly and with great force. A recent letter from the UCLA Divisional Senate's Executive Board has pointed its finger at the problem--the need for renewed state funding. It is time for the administration to do something to fix it--and something that doesn't simply damage other parts of the academic endeavor.

UCOP will continue--as they always do--to insist that we cannot get more money out of the state to pay for what needs to be done. But let's press on that point a little more. It is certainly possible that we are heading for a recession--the Federal Reserve seems determined to induce one to put labor in its place. But does that mean that the state doesn't have the capacity to respond to an emergency at the University? Despite all the talk about a budget shortfall, Dan Mitchell at the UCLA Faculty Association Blog has been pointing out that the situation is far less clear than the Legislative Analyst is insisting (and the University is repeating). For one thing, revenues have been higher than expected and that even with the possibility of a downturn the state has around 90 billion dollars in usable reserves. If the state won't help it's not because of economic necessity but a matter of political choice. After all, the Governor had no problem finding $500 million to pay for a private immunology research park at UCLA that provides little, if any, real benefit to the campus academic program. The Governor and the state can do more for the educational core of the University than they are doing: and if UCOP and the Regents can't show the state how necessary that is, then one wonders again what their purpose is.

I want to make one final point. UC is the research university of the state and UC insists that graduate education is at the heart of its purpose. But if UCOP actually agrees with that then the question must be: what do we need to do to have academic graduate education in a sustainable form? What resources do we need to enable students to both contribute to the larger functioning of the university and to pursue their studies? Are we willing to have only graduate programs where students have family money or have already flipped a startup? Or where they are here to gain an additional credential to take back to their jobs? Does UCOP remain committed to UC's contributions to disciplines across the spectrum of knowledge? Or does it only care about graduate students (and others) as cheap and disposable labor?

I don't expect that these negotiations or this strike can answer or settle these questions. But UC is at a crossroads and the university--especially its leadership--must face up to that. The long-term question raised by the strike is whether UC will continue as a research university; if we don’t make it possible for future scholars to attend, we will have forfeited our purpose. There is an opportunity here to take the first steps towards creating a new sustainable vision of a twenty-first century research university. Or we can continue as we have in decline. The choice ultimately is UCOP's and the Regents'.

****

(I've focused here on the ASE unit because the Student Researcher Unit is admittedly a more complicated problem. The vast majority of GSRs are supported by external grants and those grants have both limits and their own rules. To some extent UC has been negotiating with someone else's money. That doesn't mean the situation is impossible but rather that it has to be implemented in such a fashion as to protect Principal Investigators from damaging unintended consequences.)